"Friday last an Express arrived here

from Major Washington, with Advice, that Mr. Ward, Ensign of Capt. Trent's

Company, was compelled to surrender his small Fort in the Forks of Monongahela

to the French, on the 17th past;”

So began an article in the May 9, 1754 edition of Benjamin Franklin’s “Pennsylvania Gazette” announcing that Ensign Edward Ward of Captain William Trent’s company had surrendered his small, hastily constructed fortification in what is today Pittsburgh to a larger French force on April 17th. The major mentioned is George Washington, a young colonial officer increasingly embroiled in the British struggle with the French for control of North America. The latest struggle had been escalating for six months, when in October 1753 Virginia Lieutenant-Governor Robert Dinwiddie sent Washington to Pennsylvania to negotiate with the encroaching French. Washington returned in January empty handed. In February, to underscore the seriousness of the escalating crisis, Dinwiddie published the notes of Major Washington’s nearly 1000-mile expedition and printed them in pamphlet-form as “The Journal of Major George Washington, Sent by the Hon. Robert Dinwiddie, Esq; His Majesty's Lieutenant-Governor, and Commander in Chief of Virginia, to the Commandant of the French Forces on Ohio.” Washington’s “Journal” was subsequently published in newspapers throughout the colonies and reprinted in London several months later, where it was read with great interest by many leading figures of the British empire.

George Washington, still just in his early twenties, was making a name for himself on both sides of the Atlantic. Now that spring was again here, Dinwiddie promoted Washington to lieutenant colonel and sent him back to Pennsylvania to deal again with the French. That is how Washington’s message describing Ensign Ward’s surrender at the Monongahela was published in the “Pennsylvania Gazette.”These were all crucial events in Colonial American history, but what makes the article in the May 9, 1754 edition of Franklin’s newspaper even more important to us today was the inclusion of the accompanying “Join, or Die” political cartoon we see here.

It was one of the very earliest political cartoons published in American history. We say “one of the earliest” because there is a misconception in some circles that the “Join, or Die” cartoon is the very first. This is untrue. In November 1747 Benjamin Franklin himself had published a cartoon within a political pamphlet entitled “Plain Truth” that he had written and published anonymously as “a Tradesmen of Philadelphia” describing the state of affairs as he saw them in his city and colony.

Franklin in “Join, or Die” was calling for unity amongst British colonial subjects in the struggle against the French and their Native American allies. The cartoon was reprinted in several colonial newspapers within weeks after its initial publication. The serpent itself is a compelling choice. For one thing, the snake roughly delineates the cartography of the British colonies along the Eastern Seaboard, with New England at the head and South Carolina at the tail (Georgia being excluded). That it is a dismembered snake is also of note. British subjects in North America had always been split, with most inhabitants of the different colonies believing they shared more in common with the mother country across the Atlantic than with the residents of their neighboring provinces. Many in Franklin’s time believed that a serpent cut into pieces could rejoin its parts into a cohesive whole. Franklin’s inspiration for the dismembered snake was likely an “emblem” engraved by the French graphic designer Nicolas Verien in his 1685 book “Livre Curieux et Utile Pour Les Sçavans et Artistes.” Verien’s engraving depicts a dissected snake with the accompanying text reading “Un serpent coupé en deux. Se rejoindre ou mourir.”

British colonists in North America joining together in unity was long a goal of Benjamin Franklin. That very spring he was helping to organize what became the Albany Congress, a convention of officials from seven colonies who from June 19—July 11, 1754 met in Albany, New York to discuss a potential plan of union. In attendance too were representatives from the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy, with whom Franklin and the others were hoping to improve relations. Little came from the Albany gathering. Indeed, by the summer of 1754 even as they were meeting further military engagements between the British and French were already underway. The French and Indian War would last until 1763 with the British ultimately victorious. Benjamin Franklin’s “Join, or Die” cartoon has been repurposed continually in the nearly three centuries since its publication two hundred and seventy (270) years ago this month. Colonists used it in protest against British taxation during the 1765-66 Stamp Act crisis. Patriots throughout the American Revolutionary War created numerous variations upon Franklin’s image and accompanying text. The yellow Gadsden Flag with its coiled snake and “Don’t Tread on Me” warning is but one example.

More broadly, political cartoons became part of the American vernacular. For instance in the early 1870s William Magear Tweed, the political boss who controlled New York City’s Tammany Hall, pleaded for someone—anyone—to “Stop them damn pictures.” The “pictures” that so enraged Boss Tweed were the political cartoons created by Thomas Nast and published in “Harper’s Weekly” exposing the corruption of Tweed and his henchmen. Tweed noted that many of his constituents were themselves illiterate and thus could not read political exposés, but that there was simply no competing with the visual imagery of the cartoons that lampooned him so pithily. Benjamin Franklin had been gone for more than eighty years by this time, but he would have understood Tweed’s sentiments. As a publisher Franklin grasped the power not just of the written word, but of visual imagery itself. That is why he published “Join, or Die” in his “Pennsylvania Gazette” on May 9, 1754 to begin with. In doing so, he laid the foundation of yet another aspect of American culture and iconography.

Images:

Published in Williamsburg, Virginia in

February 1754 the month that George Washington turned twenty-two and reprinted

in London later that year, the “Journal” brought Washington to national and

international prominence in the early months of the French and Indian War.

William Hunter was Virginia’s official printer, publisher of the “Virginia

Gazette,” and since 1753 deputy postmaster general for the British North

American colonies along with Benjamin Franklin.

The “Join, or Die” cartoon, or “emblem”

as such images were called at the time, as it appeared in Franklin’s “Pennsylvania

Gazette” on May 9, 1754.

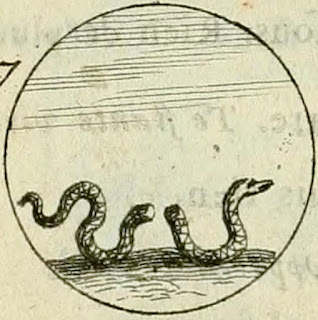

Nicolas Verien’s “Un serpent coupé en deux. Se rejoindre ou mourir.” appeared in the engraver’s 1685 emblem book “Livre Curieux et

Utile Pour Les Sçavans et Artistes.”

Keith J. Muchowski is a volunteer with

Morristown National Historical Park. This is the first in what will be an

occasional series marking events that occurred in 1754 at the outbreak of the

French and Indian War.

.jpeg)

No comments:

Post a Comment