|

| MORR 4000 A, coat, image 2022 |

HISTORY

OF THE SUIT

In

1887, the existence of a suit attributed to George Washington was brought to

the attention of the Washington Association of New Jersey, a 19th century

society dedicated to the commemoration of George Washington. Over the course of

the next two years, the Association negotiated with the suit’s owner, who had

offered to sell the suit to the Association for $400 (about $14,400 in 2023

dollars). The suit, along with a sword, two shoe buckles, and a knee buckle,

were eventually sold to the Association for a total of $180 (about $6,500 in

2023 dollars).[1] After a

brief stint on display in New York, the suit was possessed by the Washington

Association in April of 1889. The suit was, at the time of its purchase,

purported to be one worn by Washington on the date of his inauguration, 30

April 1789.

|

| WANJ display, c 1930s |

The suit, along with the sword that was purchased with it, was gifted to Lawrence Augustine Washington (Sr.), who was George Washington’s nephew by his brother Samuel. Samuel Washington died when his sons were still children, and they were remanded into the care of George Washington’s household. He raised the children and eventually enrolled them at Georgetown College. Lawrence Augustine Washington passed the suit down to his own son, a doctor also named Lawrence Augustine Washington (Jr.), who kept it in his personal collection until his death. Dr. Washington’s wife and children were able to confirm the provenance of the suit and confirm that it never left the family’s possession until its sale to the Washington Association of New Jersey.[2] [3] [4] [5] [6]

When Morristown National Historical Park was founded in 1933, the Washington Association of New Jersey donated the Ford Mansion, the property, and their collection of books and artifacts to the National Park Service, including the suit. In the years that followed the acquisition, the Park Service went about confirming the origins of the suit and preparing it to be displayed to the public. This included ordering a custom mannequin and employing the services of a garment restorer. The person tasked with making repairs to the suit was Madame Helene M. Fouche of New York City, who was hired on the recommendation of the Museum of the City of New York.[7] In 1937, the suit was sent to the city for cleaning and repair, and its fragile condition was noted in the minutes recorded by the Washington Association.[8]

Madame Fouche made some observations about the condition of the suit: “...it certainly was a disappointing work…if it had not been such [a] relic I think I would have given up.” She goes on, “The material is all decayed and can not be moved, however little, without breaking.” She advised displaying the suit laying flat, so as not to further damage the fibers.[9] Fouche’s work on the suit included cleaning and strengthening the weak spots on the very delicate silk. These repairs included taking some fabric from inside the coat and using it to recover the buttons which at that point were very damaged.[10] Madame Fouche quoted a rate of $15 - $25 for the cleaning, with an additional $6.00 per day for repairs, although the final receipt was not located in our research.

|

| Federal Hall displace, c. 1970 |

In 1972, more repairs were made to the suit, which included surface cleaning and stabilization of long-term damage to the suit. These repairs were made throughout the coat, waistcoat, and pants using human hair thread and silk crepeline, and also using the lining of the coat as the source of the repair fabric.[13] Many of Madame Fouche’s repairs were removed and replaced using techniques that were more advanced than what was available in the 1930s. Later assessments by textile conservators in the 1980s and 1990s determined that the suit had sustained considerable deterioration and special measures would have to be taken to keep it stable.

After

70 years of continuous exhibition between MNHP and Federal Hall, the suit was

determined to be too badly deteriorated to continue displaying to the public

and it was removed for further assessment and safe storage. It remains in

secure, climate-controlled storage at Morristown National Historical Park

today. Regrettably, the cost of stabilizing the suit and creating a

state-of-the-art display is incredibly high, and it might be many years before

the suit can be repaired and displayed again.

WHAT

WASHINGTON WORE: THE POLITICS OF THE INAUGURAL SUIT(S)

|

| Inauguration of George Washington wearing the broadcloth suit by De Elorriaga (1889) |

The oral tradition that came with the suit suggested that it was worn by George Washington on his inauguration day. The owners of the suit, and for many years the museum itself, believed that the suit was none other than the one that was worn by Washington as he was sworn in at Federal Hall in New York City, making it a very important piece of fashion history. Many contemporary accounts noted that the inaugural suit was brown and, knowing that our suit is also brown, the original story seemed to fit. However, as further research was conducted into accounts of Washington’s inauguration, it was noticed that the inaugural suit was actually made of broadcloth - a dense, plain woven cloth of wool and linen. The brown broadcloth suit also featured bronze buttons with eagles. Conversely, the suit owned by the national park is a much lighter buff silk, with covered buttons that match the material of the suit.

In the short time between his election and his inauguration, Washington was acutely aware that every choice he made as president would be highly scrutinized - including the details of the inauguration. Washington had two shrewdly calculated goals: to avoid acting or looking like a king and to support an American industry. In doing these things, the new President could be seen to support local manufacturing and, perhaps more importantly, embody democratic principles in a material way. For this purpose, Washington employed the expertise of Henry Knox:

….Having learnt from an Advertisement in the New York Daily Advertiser, that

there were superfine American Broad Cloths to be sold at No. 44 in Water

Street; I have ventured to trouble you with the Commission of purchasing enough

to make me a suit of Cloaths. As to the colour, I shall leave it altogether to

your taste; only observing, that, if the dye should not appear to be well

fixed, & clear, or if the cloth should not really be very fine, then (in my

Judgment) some colour mixed in grain might be preferable to an indifferent

(stained) dye. I shall have occasion to trouble you for nothing but the cloth

& twist to make the button holes. If these articles can be procured &

forwarded, in a package by the Stage, in any short time your attention will be

gratefully acknowledged...If the choice of these cloths should have been

disposed off in New York—quere could they be had from Hartford in Connecticut

where I perceive a Manufactury of them is established…”[14]

The manufactory that Washington refers to is the Hartford Woolen Manufactory, which was founded in 1788 by Jeremiah Wadsworth and Peter Colt. Around the time of this communication, Wadsworth had launched a massive advertising campaign hawking their fabrics, creatively naming them in the spirit of the time - such as “Congress Brown.” Wadsworth intentionally framed buying American-made goods as an act of patriotism, and aggressively lobbied prominent leaders and politicians to wear his goods.[15]

Washington wrote this to Daniel Hindale, an agent of the Hartford Woolen Manufactory:

“....I am extremely pleased to find that

the useful manufactures are so much attended to in our Country, and with such a

prospect of success……I am fully persuaded that if the spirit of industry

economy and patriotism, which seems now beginning to dawn, should exert itself

to a proper latitude, that we shall very soon be able to furnish ourselves at

least with every necessary and useful fabrick upon better terms than they can

be imported without any extraordinary legal assistance—I shall allways take a peculiar

pleasure in giving every proper encouragement in my power to the manufactures

of my Country…”[16]

|

| Example of broadcloth suit at Mount Vernon, a contender for the swearing in suit. Image courtesy of Mount Vernon. |

After several months of exchanging letters, drawings, and samples with the manufactory, Washington settled on the famous “Congress Brown” broadcloth, but of a fine quality that resembled velvet. The color was a deep, sober brown and conveyed a republican rejection of the brighter pinks and blues that were popular in the Empire. Henry Knox fretted over Washington’s choice because it was too coarse and common. The suit took several months to complete, with work performed on the garment up until the very last minute. Ultimately, despite Knox’s discouragements, the brown suit was completed on time and he wore it.[17]

Yet…it did not have the effect that Washington hoped. The witnesses of Washington’s first inauguration did not see American simplicity; rather, they saw a “finely cut, glazed, and deep brown suit that they had every reason to assume was imported.”[18] Indeed, many people mistook the broadcloth for a fine velvet. This mistake resulted in political criticism of Washington, in which his personal virtue and political loyalty were questioned. The Pennsylvania Gazette wrote:

“As an indulgence in a single vice must prevent a man from being deemed really virtuous, so ought a perseverance in a line of conduct, detrimental to national happiness, to preclude him from the name of patriot…We we see a citizen, who has frequently exposed his life in the cause of freedom, dressed in manufactures of foreign nations, have we not reason to suppose, that either he does not understand the welfare of his country or that he totally disregards it?”[19]

Another paper, the Gazette of the United

States, later attempted to correct the record, noting that Washington’s

suit was in fact American homespun, but the political damage had already been

done. The manufacturers had worked so hard to produce a high quality product

that, in their success, caused the garment’s symbolism to fail.[20]

So

what of the suit at Morristown National Historical Park? The silk suit that

MNHP possesses is not the broadcloth

worn early on the inauguration day. It is far more likely that the silk suit is

a garment that was worn after the public daytime events, into which Washington

would have changed to enjoy more private evening celebrations, however there

are no documents besides the oral history of the garment that articulate that

fact. What can be certain is that the

suit was in fact owned and worn by Washington. The dimensions are correct based

on his other surviving garments and the suit never left the possession of

Washington’s descendants until it was owned by the Washington Association of

New Jersey.

|

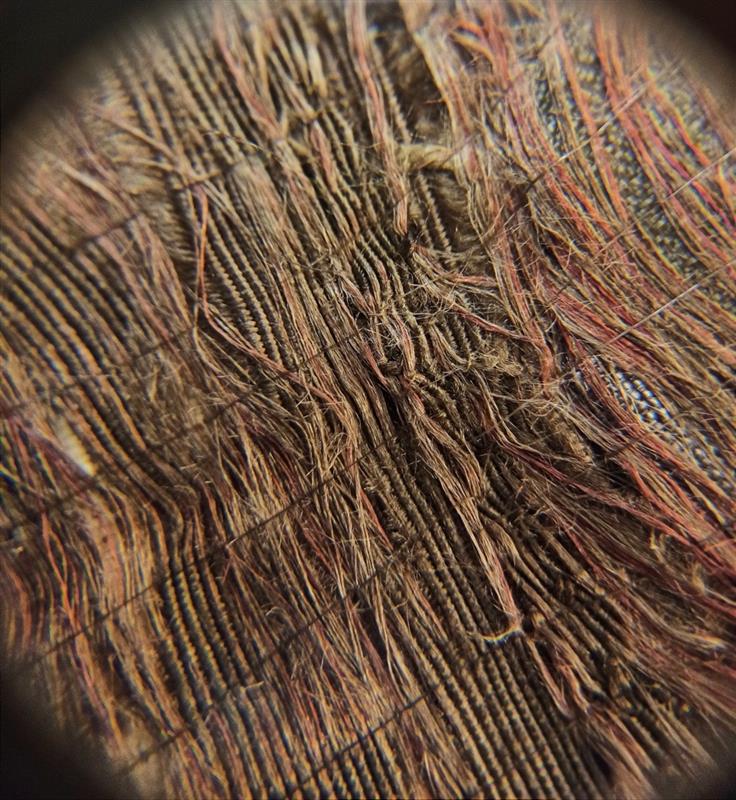

| close up showing pink thread |

The material of the suit aligns with the assessment of evening wear and each

piece of the suit is made out of the same buff silk. “Buff” refers to a

particular shade of a light brown with yellowish tones. When it was

manufactured, the silk would have been a very pale tan, although it has

darkened considerably with age. The silk retains much of its sheen today, and

it would have been especially beautiful at the time it was worn. Interestingly,

many of the horizontal fibers (the “weft”) were dyed pink. The effect of this

was a lustrous cream color that, in the right light, would have shone with pink

iridescence. The pink sheen is still evident, and the threading is especially

vibrant underneath a magnifier.

The styling of the suit also indicates that it would have been meant for

evening wear. Silk was a high-end material that would have been regularly worn

as formal attire by a man of Washington’s status, and a material that

Washington would not have likely worn during his “working” hours. The color of

the silk is also appropriate; formal clothing was often brightly colored in the

18th century, although dark colors would eventually displace this in the 19th

century.[21] Although

the

suit is made from an incredibly rich material, it is relatively unadorned

and the cut favors simplicity. These design choices were influenced by the

popularity of Neoclassicism, which favored plain fabrics and clean lines.[22]

Furthermore, the long coat skirt, tightly fitted sleeves, and standing collar

were popular fashions in both England and America in the 1780s.[23]

Washington would continue to use sober and unadorned clothing as his state

attire, trending towards darker colors in the later years of his Presidency.[24]

After the inauguration, Washington and his party walked to St. Paul’s Chapel on Broadway, where the Episcopal Bishop of New York led a special service. This was the last “public” event of the day, and Washington retired to the Presidential Mansion for a private dinner, alone. What he did in those hours is not known, but it is likely that changed from his wool suit into his finer silks and joined the evening celebrations.[25] That night, New York City was a feast of lights, with displays of artful illuminations on ships, rooftops, and in thousands of windows. Fireworks were set off for hours and hours, and were the primary entertainment of the evening; which Washington and his aides watched from the homes of Chancellor Livingston and Henry Knox.[26] Notably, there was no inaugural ball that night. A ball was held, however, a week later and many notable people attended including the President. Although we were unable to locate accounts of his clothing that night (or at the many balls and banquets in the following weeks), it is absolutely possible that he wore the silk suit again. Indeed, such an expensive garment would have certainly been worn more than once and the “wear-and-tear” on the seat of the breeches suggests just that.

|

| MORR 4000 B, vest |

Washington’s fancy silk suit would have added to the confusion and tensions surrounding the mistaken identity of his broadcloth inaugural suit, and this suit left no doubts about its imported (and British) origins. Of this, historian Linzy A. Brekke writes: “...the two-faced nature of Washington’s clothing performance led to further public condemnation. What had begun as an attempt to help construct and symbolize self-sufficiency and national identity wound up accurately, if unintentionally, signaling the cultural confusion, fragmentation and transatlantic dependency of American life.”[27]

|

| MORR 4000 C, pants |

CARING FOR A HISTORIC GARMENT

|

| close up of coat button repair |

|

| 20th century repair areas in the back of the suit coat |

From 1937 to 1971, the suit was displayed at the museum on a custom mannequin in a new glass case. Although it was better protected from fluctuations in temperature and humidity, it was still exposed to direct light by way of tubular incandescent lights (which were eventually replaced by fluorescent lights). An evaluation of the suit in 1972 noted that the light exposure likely contributed to aging and “increased degradation” of the suit.[28] In the 1970s, the suit was loaned to Federal Hall as part of a bicentennial exhibition, in which it was placed on a custom form in a wood and plexiglass case. Staff did not have easy access to the suit and maintenance was largely neglected for an extended period of time. The suit was also, at this time, exposed to continuous fluorescent lighting.[29]

|

| conservators examining MORR 4000 C, pants |

|

| vest shown on its stabilization mount and filled with supportive pillow |

The museum and textile conservator developed a storage plan for the suit that would provide necessary support for the garment in long-term storage, but also allow it to be occasionally removed for conservation evaluations and special displays.[31] To do so, a passive system of mounting and storage was developed to reduce the need for direct handling. Each garment was placed on a specially cut and padded board and a supportive pillow was placed inside each garment to prevent its collapse over time.[32] While in storage, the suit lays totally flat, and each part is wrapped in ripstop ethofoam and batting forms to prevent movement.

|

| conservators unbox the suitcoat for the first time since 1992 |

|

| examples of shattered (L) and in-tact (R) silk close ups taken from the pant leg. |

[1] Author Unknown, Park Research Memo, Ca.

1930s-1940s [located with correspondence in 1889-1910 file].

[2] Martha D Washington, “Valuable Relics of

Washington for the Headquarters,” 12 April 1889. Notarized by W.H. Robert Jr in

Grayson County, TX.

[3] Elbert Cox, Letter to Erskine Kerr, 27

February 1939.

[4] Bushrod W. Fontaine, Letter to Cora Wilson, 7

December 1937.

[5] Shirley Washington Fontaine von Meyer, Letter

to Elbert Cox, 8 December 1937.

[6] Bushrod W. Fontaine, Letter to Cora Wilson,

14 June 1941.

[7] Elbert Cox, Letter to Helene Fouche, 27 April

1937.

[8] Washington Association of New Jersey,

“Reports and Abstract Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Washington

Association of New Jersey,” 23 June 1937, 6.

[9] Helene

M. Fouche, Letter to Elbert Cox, 27 May 1937.

[10] Helene

M. Fouche, Letter to Elbert Cox, 8 May 1937.

[11] J.W. Rice, “George Washington’s Suit Gets

Another Conservation Treatment” [Park Service Draft], 22 September 1972.

[12] Rice, Ibid.

[13] Helene von Rosenstiel, “Conservation

Assessment of Inaugural Suit of George Washington,” Helene von Rosenstiel,

Inc., 1989.

[14] George Washington, Letter to Henry Knox, 29

January 1789. Located at:

https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-01-02-0197

[15] Linzy A. Brekke, Fashioning America: Clothing, Consumerism, and the Politics of

Appearance in the Early Republic (Dissertation: Harvard University, 2007),

28.

[16] George Washington, Letter to Daniel Hindale,

08 April 1789. Located at: https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/05-02-02-0040

[17] Brekke, Fashioning

America, 29 - 31.

[18] Ibid., 33.

[19] Pennsylvania

Gazette, 15 April 1789.

[20] Brekke, Fashioning

America, 34.

[21] Linda Buamgarten, Eighteenth Century Clothing at Williamsburg (Colonial Williamsburg

Foundation, 1986), 61.

[22] In the period following the Revolution, many

Americans looked to Ancient Greece and Rome for intellectual and cultural

inspiration - a movement called Neoclassicism. This movement also spilled over

into popular fashion for people of all social strata.

[23] Brekke, Fashioning

America, 35.

[24] Diana de Marley, Dress in North America, Vol. I (NY: Holmes & Meier, 1990), 166

- 167.

[25] “President Washington’s Inauguration: April

30, 1789,” George Washington’s Mount Vernon,

https://www.mountvernon.org/george-washington/the-first-president/inauguration/timeline/#-.

[26] “President Washington’s Inauguration: April

30, 1789,” George Washington’s Mount Vernon,

https://www.mountvernon.org/george-washington/the-first-president/inauguration/timeline/#-.

[27] Brekke, Fashioning

America, 34.

[28] J.W. Rice, George Washington’s Suit Gets

Another Conservation Treatment [Draft], 22 September 1972.

[29] Helene Von Rosenstiel, “Report of On Site at

Federal Hall NYC,” Helene Von Rosenstiel,

Inc., 11 September 1989.

[30] Superintendent Morristown National Historical

Park, Memorandum, 7 August 1992.

[31] Deby Bellman, “Passive Supports for

Textiles,” Conserving Museum Collections,

CRM: 22.7 (1999), 22-23.

[32] Ibid., 23.

[33] Windsor Conservation Report on George Washington’s Suit, completed December 2022.

This post by Amy Hester, Museum Technician

No comments:

Post a Comment