|

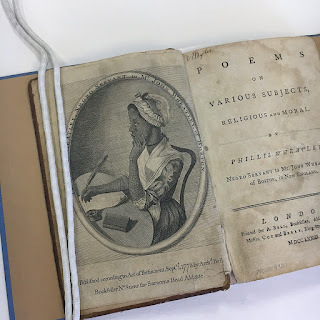

| Features the title pages, the left, an engraving of Wheatley at her writing desk. Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral.” MORR 9321 |

Last year, the park recovered a special document from its

archival collection – a rare, first-edition copy of Poems on Various

Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773). This edition is particularly special

because it bears the signature of the author, famed poet, Phillis Wheatley. In

October, the curatorial staff presented this special document in collaboration

with Maestro Robert Butts of the Baroque Orchestra of New Jersey, who arranged

music inspired by the collection. It is our goal to continue to work with this historic

document and develop programming around it. To do so, we must imagine ways that

the park can engage this piece in an ethical way that is in-keeping with

contemporary scholarship on race, slavery, and Wheatley herself.

Some readers may know Wheatley from their middle school

history textbook, some may have read her in a college literature course, others

– perhaps many – may not have heard of her at all. Unfortunately, we are taught

too little of Phillis Wheatley, only given short biographical sketches. These

biographies are usually told in four parts: She came to America as a slave, was

far more educated than her African peers, became a published poet, and was

“kindly” emancipated by her masters. We are taught that she was the first

published African American poet, that she was uncommonly brilliant, that she

proved her brilliance to a jury of Boston’s greatest minds, and that she met

George Washington. Of those, we can only be sure of two things: that she was

undoubtedly incredibly well-educated and intelligent, and that she was the

first published African America writer. Although we celebrate Washington a

great deal here in Morristown, their meeting is actually unverified. Upon

reflection, however, it is clear that this story is not very reflective of her

life, or of the dynamic, three-dimensional person that she certainly was.

Phillis Wheatley’s life and works are by far richer and more complicated than we

are ever taught.

|

| Wheatley's signature close up. |

So, then, how are we supposed to know Wheatley? How do we listen to the silences of her story and reimagine the depth of her character? This is a question that is of vital importance to historians, particularly in regard to the lives of the millions of enslaved Africans whose voices and stories are irretrievably lost. In Wheatley’s case, we are fortunate that she left behind her poetry and an assortment of letters, which document many of her thoughts, although these are scattered and hard to come by. However, having documentation of her life does not mean that she was an exception to the mass erasure of black voices. We are left with only pieces to a puzzle that we must reassemble and reimagine what belongs in the empty spaces.[1]

We should start with one troubling fact: we do not know her

name. We know her as Phillis Wheatley, of course, but this was not the name

that she was born with. Her entire identity was supplied to her by slavery: she

was named after the ship that brought her – the Phillis – and the

family that enslaved her – the Wheatleys. Neither do we know where she was born

and raised, how she came in the hands of European traders, what became of her

family, or what her experience was during the Middle Passage.[2]

The person that she had been, as with the majority of enslaved people, was

completely erased. With the erasure of her past so too came the erasure of the

person she could have been, had she remained in her homeland.

Just by reading schoolbook biographies, we know little of her

life as a child in the Wheatley household, like why the Wheatleys supplied her

with such an extensive education and what their bonds of affection were. Even

after decades of study, no historian can truly answer why the Wheatleys were so

protective and affectionate to Phillis or why they even brought her home to

begin with. Their objective, after all, was to obtain a servant and a small

sickly child like Phillis was not a usual candidate.[3]

The closest thing we have to an answer to this question is speculation that the

child they first encountered may have reminded them of their youngest daughter,

recently deceased, who was about the same age. Still, despite their undoubtable

affection for Phillis, they did exploit her talents as she grew older.[4]

Boston was different than the slave society of the South, and enslaved people were allowed to be baptized, marry, and become literate – but only at the discretion of their “masters.” Slaves in New England lived in much closer proximity to their masters, which might have afforded a marginally higher level of material comfort but came with the expense of constant surveillance and increased vulnerability to abuse. The Wheatley’s owned a significant amount of property, including other slaves. They were unique in this regard as only 3% of Bostonians held all of the slaves in the city. Phillis was not permitted to interact with other black servants, and certainly not any others that may have been in the area.[5] In fact, a man of African descent also enslaved by the Wheatleys, was punished for merely sitting next to her. Yet, Phillis was not equal to the Wheatleys’ white high society peers and though she socialized with them, she was known to sit at separate tables. Aside from her close relationship with the Wheatleys, Phillis had a secluded adolescence.[6]

Within four years of her arrival in Boston, by the age of eleven, Phillis was literate in the English language and began her first attempts at writing verse. She was educated by Susannah and perhaps went to school with Mary, her daughter. Her proximity to a vibrant religious community also exposed her to literacy. In New England Congregationalism, literacy was encouraged as a path to religious conversion and salvation. The Wheatleys were enthusiastically religious and their wealth and social status brought them in close contact with high-ranking religious leaders. As a child and young adult, Phillis attended sermons by a great number of preachers, many of whom she later established correspondence with. Phillis’s keen intellect and elite education was a novelty to the Boston literati and the Wheatleys took advantage of this novelty, using Phillis to demonstrate their piety, charity, and successful effort to convert a slave in in their household – further reinforcing their choice to sponsor her education. She was published for the first time by age 13, and internationally known by the age of 17.[7]

It is clear, though, that Phillis’ religious beliefs were earnest and sincere. Religion was, naturally, the core subject matter of her poetry and defined most of her intellectual relationships and literary career. Phillis’s poems were not merely the musings of a religious woman and reading her poetry solely in this context only skims the surface of her true skill. Rather, her poems were rebellious, subversive, and cleverly coded to avoid reprisal. Indeed, she wrote poems directed to those of a higher station than she and presumed to teach them about life and religion. And she did – as her poetry enjoyed increased popularity she was sought after for commissions. More important, perhaps, is Wheatley’s use of religious rhetoric to address the subjects of race, slavery, and freedom – which were controversial topics for even white writers to address, much less the enslaved themselves. She used her poetry to remind her almost entirely white audience that enslaved Africans were just as able and worthy of redemption as themselves. Biblical struggles for freedom, the importance of endurance for victory, faith as armor, and the heroism of marginalized characters are all devices she used that highlight a preoccupation with the oppressive nature of slavery and a desire to engage with it. She also employed the language of the Revolution to address the increasingly challenged place of slavery in the fight for political independence and she hoped to convince the political powers of the day that preserving a slave state contradicted their desire for freedom from Britain. Poetry was an important act of resistance for Wheatley that delivered a direct challenge to an oppressive system. [8] [9] [10] [11]

When Boston publishers refused to publish her first collection, she traveled with John’s son Nathaniel to London to make an appeal to British publishers. There, Phillis was a celebrity, hosted by English aristocracy, diplomats, and famous abolitionists. England, by this point, had also passed a landmark judicial decision against slaveholders – while slavery was still technically legal in Britain, slaveholders did not have the right to coercively transport them in England or to the colonies. This meant that enslaved people could legally emancipate themselves by leaving their master on British soil. Phillis certainly knew this, as she was personally acquainted with the architect of the ruling, yet she chose to return to Boston as an enslaved woman. She was manumitted shortly after her publication, and it is possible that she leveraged her powerful connections to guarantee her freedom upon return to Boston.[12] [13]

Phillis’s adult life, lived as a free woman, is another

poignant silence in her biography – very little is known about the time

following her release from the Wheatley household. We know that, despite her

international fame, she was unable to publish a second volume of her poetry.

The Revolutionary War and the economic depression that followed significantly

disrupted her network of readers and supporters. Yet, she continued to write

poetry, publish in broadsides, and maintain her correspondences with notable

people of the day. We also know that she married a man named John Peters.

Peters was an unusually educated black entrepreneur with many inconsistently

successful business ventures. Money was tight for the couple for many years and

Peters did not obtain his fortune until years after Phillis’s death. Phillis

Wheatley died in 1784 with no living children. Unfortunately, many of her

personal papers have been lost to time, including a number of her poems.[14]

Listening to the silences of her later life is an ongoing task. A scarcity of documents compounds the difficulty of getting to know the adult Phillis. This is a job for contemporary and future historians, but also for all of us here today. Phillis Wheatley was a woman of tremendous depth, whose story is rarely done justice. We should also use this as an opportunity to consider the silenced historical voices of the millions of other enslaved African Americans who are not the subjects of scrutinized biography. It is my hope, however, that our ongoing project will be a small – but improved – step in the right direction.

Listening to the silences of her later life is an ongoing task. A scarcity of documents compounds the difficulty of getting to know the adult Phillis. This is a job for contemporary and future historians, but also for all of us here today. Phillis Wheatley was a woman of tremendous depth, whose story is rarely done justice. We should also use this as an opportunity to consider the silenced historical voices of the millions of other enslaved African Americans who are not the subjects of scrutinized biography. It is my hope, however, that our ongoing project will be a small – but improved – step in the right direction.

[1]

Robert Kendrick, “Phillis Wheatley and the Ethics of Interpretation,” Cultural

Critique 38 (1997), 39-64.

[2]

Vincent Caretta, “Phillis Wheatley: Researching a Life,” Historical Journal

of Massachusetts 43.3 (2015), 65 – 66.

[3]

Eleanor Smith, “Phillis Wheatley: A Black Perspective,” The Journal of Negro Education 43.3 (1974), 401 – 402.

[4]

Vincent Caretta, Phillis Wheatley: Biography of a Genius in Bondage (Athens:

University of Georgia Press, 2011),

[5]

Eleanor Smith, “Phillis Wheatley: A Black Perspective,” 403.

[6]

Vincent Caretta, Phillis Wheatley: Biography of a Genius in Bondage, 11

-27.

[7]

Ibid., 28 – 42.

[8] Ibid.,

68 – 93.

[9]

Antonio T. Bly, “‘On Death’s Domain Intent I Fix My Eyes’: Text, Context, and

Subtext in the Elegies of Phillis Wheatley,” Early American Literature 53.2

(2018), 317 – 341.

[10] James

Edward Ford III, “The Difficult Miracle: Reading Phillis Wheatley against the

Master’s Discourse,” The Centennial

Review 18.3 (2018), 181 –

223.

[11]

David Waldstreicher, “Ancients, Moderns, and Africans: Phillis Wheatley and the

Politics of Empire and Slavery in the American Revolution,” Journal of the

Early Republic (2017), 701 – 733.

[12]

Vincent Caretta, “Phillis Wheatley: Researching a Life,” 66 -68.

[13]

Henry Louis Gates, The Trials of Phillis Wheatley: America’s First Black

Poet and Her Encounters with the Founding Fathers (New York: Civitas

Books), 17.

[14]

Vincent Caretta, “Phillis Wheatley: Researching a Life,” 69 – 72.

This blog post by Amy Hester, Drew University.

No comments:

Post a Comment