Who would have thought that removing 17th century manuscripts, glued down to acidic paper, would actually feel like an operation?!

My experience as an intern at Washington’s Memorial Headquarters was nothing short of inspiring and intriguing. My job as an intern was to process and rehouse scrapbooks from Lloyd W. Smith. There are about 30 scrapbooks in his collection and all of them are glued down onto ridiculously acidic paper that is burning the manuscripts from the inside-out. Handling 17th century manuscripts that have not been touched in 50+ years was one for the books. I knew I had a daunting task ahead of me.

To me, research is an ambiguous word. Some people think about reading pages upon pages of books and letters to educate themselves on a specific topic they are studying. That is what I thought research was until it came time to dissemble these scrapbooks. My research consisted of dissecting each manuscript. I tried to figure out who the letter was from/to, the date, the language, the context behind it, and why Smith specifically placed it in the order that he did. Was each document connected to the one following it? Were they completely random and did he place them there because he thought they were unique? Some of these questions I was able to answer and some of them I was not. If there is a word to describe someone who is more than a perfectionist, I would be the definition of that word! I am curious and constantly searching for answers. It was challenging and frustrating to retrace the steps of someone as mysterious as Smith because I did not always discover the answers I was looking for. It was also challenging because the first scrapbooks I tackled were titled the “Thirty Years War”. After 3 months of reading Dutch, Swedish, Latin, and German, I can officially confirm that I am not fluent in any of these. How could I possibly do research, successfully, in different languages? Luckily this type of research did not consist of as much reading as I initially thought. I was able to identify context clues to help me. I think my generation was one of the last one to be taught cursive in elementary school but was not forced to continue with it after that. As sad as this is to say, I am thankful that I actually remember the entire alphabet. I thought knowing basic cursive would be beneficial for me when reading 17th century paleography. Well, I was gravely mistaken. Languages and handwriting have evolved so much in the past 400 years that the “1”, “7”, “S”, “R”, and “T” looked way different back then than they do now.

This manuscript gives you a glimpse of the paleography I was handling. As elegant as it appears, do not be deceived by its undecipherable letters.

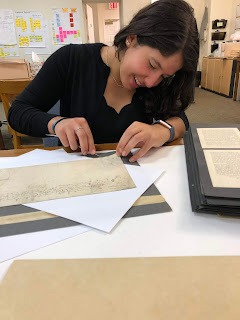

I thought that archival processing was difficult until it came to archival preservation. One of the most frustrating parts about removing these ancient documents was that the collector casually glued these precious and priceless artifacts to acidic paper. For someone who appreciates and loves history as much as I do, this was tragic to look at, let alone dissemble. As shown in the photo, I used a scalpel and a scissor to remove most of the manuscripts and engravings. The majority of the documents were glued down in all four corners. Some of the manuscripts already had the first layer peeled off but others were still completely glued down.

If the manuscript was completely glued down, painfully, I would have to sacrifice it to the acidic paper furnace and just make a copy onto non-acidic paper and place it into the appropriate folder. The hardest removal I had was removing two primary documents completely glued down on the same corners. They were the same exact size as well. Although I did not feel completely comfortable removing them, I also did not feel comfortable leaving them to decompose. I designed a couple of contraptions out of paper and foam in order to create a barrier between all three surfaces. After about 15 minutes of careful cutting, I successfully removed both with minimal acidic paper left behind. I uncovered that sometimes the best practices are the most abnormal or unusual ones. Archival preservation will always have its complications, but it is important to be versatile and think outside of the box.

The

final step to my internship was to create a finding aid. A finding aid is a

tool used to facilitate research for others. It is that excel spreadsheet or

document that you come across while trying to discover what is actually in a

museum or library without physically being present there. In my experience of

doing research, I was always too focused on my project and never realized how

much effort goes into creating an accessible research platform for others.

Being the woman behind the scenes for creating the finding aids was stressful

but so fruitful. Whenever classmates are out of class for a day and ask for my notes,

I always tell them to ask someone else. Simply because I have the messiest and

most disorganized notes you probably have ever seen. My brain processes

research and lectures in a very scattered and disorganized way. When I review

my notes, it makes sense to me, but not to everyone else. Creating the finding

aid challenged me to think like the person on the other side of the screen who

thinks completely different than me. Where would they look for a date or a

specific detail about the manuscript or the type of manuscript it is? I learned

how important it is to be effective and organized in your work.

It is

mind-blowing to me that hundreds of people will be viewing this finding aid and

my work might have an impact on their research or the way they perceive

history.

This blog post by Madeline Narduzzi, University of Dallas.

No comments:

Post a Comment