Please Note: As of April 25, 2025, this blog will no longer post new material. We are however, keeping the site available for review and research. Thank you.

Friday, April 25, 2025

Monday, March 31, 2025

The Federalist Papers

Follow this link to read a post in the Journal of the American Revolution about the Federalist papers.

This post is by Morristown NHP chief of cultural resources Dr. Jude Pfister.

https://allthingsliberty.com/2025/03/the-federalist-papers/

MORR 11744, Volume two, first edition, first imprint

Tuesday, December 3, 2024

SiriusXM radio interview

Tuesday, October 8, 2024

President Washington and the Beginnings of American Law

Follow this link to read a post in the Journal of the American Revolution about President George Washington and the Beginnings of American Law.

This post is by Morristown NHP chief of cultural resources Dr. Jude Pfister.

https://allthingsliberty.com/2024/10/president-washington-and-the-beginnings-of-american-law/

You can listen to a podcast with Dr. Pfister about this topic here:

Monday, September 9, 2024

The Whiskey Rebellion of 1794

President George Washington delivered his sixth annual message to the U.S. Senate and House of Representative on November 19, 1794. In his opening paragraph he proclaimed that “with the deepest regret do I announce to you that during your recess, some of the Citizens of the United States, have been found capable of an insurrection. It is due, however, to the character of our Government, and to its stability, which cannot be shaken by the enemies of order, freely to unfold the course of this event.” Washington was referring to what is today called the Whiskey Rebellion, an uprising of some 7,000 farmers and distillers that had taken place in Western Pennsylvania earlier that summer and fall. The protesters’ anger was over a tax on distilled spirits put in place a few years previously. Washington himself explained in his message to the legislators that “During the Session of the year 1790—it was expedient to exercise the legislative power, granted by the Constitution of the United States, “to lay and collect excises.” In a majority of the States scarcely an objection was heard to this mode of taxation. In some indeed, alarms were at first conceived; until they were banished by reason and patriotism. In the four western Counties of Pennsylvania a prejudice, fostered and embittered by the artifice of men who laboured for an ascendancy over the will of others by the guidance of their passions, produced symptoms of riot and violence.”

The roots of the crisis dated back to

January 1790, when in his "Report Relative to a Provision for the Support

of Public Credit" Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton proposed an excise

tax on, among other things, distilled spirits. Hamilton’s recommendation became a reality the following year with

the passage on March 3, 1791 of “An Act repealing, after the last day of June next, the

duties heretofore laid upon Distilled Spirits imported from abroad, and laying

others in their stead; and also upon Spirits distilled within the United

States, and for appropriating the same.” Its long-winded title may sound dry,

but the whiskey tax the bill created outraged citizens of not just Western

Pennsylvania but Virginia, parts of New York, regions of what would become the

state of Kentucky, and essentially any other community where residents

manufactured distilled beverages. The act would later be amended slightly but

amounted usually to a tax ranging from six (6) to eighteen (18) cents per

gallon—with revenues to paid in cash, a great burden in rural regions where

hard currency was usually in short supply. Taxes were collected at the point of

manufacture by local inspectors. The way the system was structured small

manufacturers paid rates high than those of larger distillers, a fact not lost

on yeoman workers.

Federal distillery tax book for Tennessee, 1796-1801

Public outcry increased exponentially

in the months and years after passage of the excise law. Several dynamics

created such passion. Distilled spirits in the New World had its roots in the

British Isles, from where the Scots-Irish in America drew their cultural

heritage. Moreover, in a budding nation with so little infrastructure taverns

were more than mere drinking establishments; people congregated in them to

gossip, talk business, gather news, sometimes pick up their mail, or even spend

the night if they were traveling. Financially, as mentioned, the tax was a

particularly heavy burden for rural distillers working on narrower economies of

scale compared to their larger competitors in cities back East. The taxes

having to be paid in cash was an extraordinary burden in what was essentially a

frontier barter economy. What is more, any legal proceedings were to be held in

Philadelphia, some three hundred miles away from the four most rebellious

Pennsylvania counties west of the Alleghenies. That region’s remoteness was

itself one reason for the distillation of wheat into whiskey. The liquid

beverage was simply easier to transport across long distances—and thus more

cost-efficient—than the grain itself. Legal proceedings being held so far from

home had a strong whiff of the British courts that colonists complained about

in the Declaration of Independence. One line in the Declaration had admonished

the British Crown “For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended

offences.” Distillers also viewed the tax in the context of the levies put in

place by King George III in the 1760s and early 1770s prior to the Revolution,

in some communities even running up liberty poles in protest against the

whiskey tax in reference to those protests against the British years

previously. Politically, the whiskey tax was becoming entangled in the growing

disputes between Federalists like Hamilton and emerging Democratic-Republicans

led by Thomas Jefferson.

President Washington initially tried the soft approach. On September 15, 1792 he issued a proclamation reading in part that “Whereas certain violent and unwarrantable proceedings have lately taken place, tending to obstruct the operation of the laws of the United States for raising a revenue upon Spirits distilled within the same, enacted pursuant to express authority delegated in the Constitution of the United States . . . Now therefore I George Washington, President of the United States . . . most earnestly admonish and exhort all persons whom it may concern, to refrain and desist from all unlawful combinations and proceedings whatsoever.” The unrest however continued, including with the tarring-and-feathering and other acts of violence and intimidation against excise tax collectors.

Tarring-and-feathering of an excise officer

The crisis reached a

turning point with an attack on the person and property of one John Neville,

the wealthy and deeply unpopular collector in Western Pennsylvania. On July 16,

1794 Neville successfully beat back the mob with the assistance of the enslaved

community on his estate. The following day a mob of between 500-600 returned

once again and burned down Neville’s home, Bower Hill. Washington and his

Cabinet were divided and on August 2 the chief executive held a conference in

Philadelphia, the nation’s capital, to gather advice from both federal and

state officials. On August 7 the president issued another proclamation “command[ing]

all persons, being insurgents as aforesaid and all others whom it may concern

on or before the first day of September next to disperse and retire peaceably

to their respective abodes.” The president and his advisors continuing

monitoring events closely. When September 1, 1794 came and went with little

result Washington knew he finally had to do something. He released yet another

proclamation, on September 25, 1794, announcing that “the moment is now come”

to take military action. President George Washington then personally led nearly

13,000 men into Western Pennsylvania to quell the Whiskey Rebellion. It was the

first and only time a serving president personally commanded troops in the

field.

Militarily the excursion into Western

Pennsylvania in fall 1794 was anti-climactic. Indeed it was over almost as soon

as it began, with rebels in community after community evaporating prior to the

arrival of President Washington and his militia. It was so uneventful that the

commander-in-chief eventually returned to Philadelphia and left others in

charge. Still, when President Washington delivered his message to Congress on

November 19 the matter was not entirely over. There was the issue of what to do

with the 150 or so individuals arrested. Most were let go without trial, and

about a dozen eventually tried for treason. Of those, two were convicted.

Washington pardoned most of the Whiskey Rebellion insurrectionists, including

the two convicted individuals, in 1795, the first presidential pardons in

American history. The whiskey tax itself remained in place until 1802 when

Congress with President Thomas Jefferson’s encouragement repealed the unpopular

measure.

Images:

An 1863 interpretation of the

tarring-and-feathering of a 1790s whiskey excise tax collector; via New York

Public Library Digital Collections

This page from a federal distillery

tax book covering the years 1796-1801 in Tennessee is a reminder that the

whiskey tax was in effect even after the 1794 rebellion; courtesy Tennessee

Virtual Archive.

Keith J. Muchowski volunteers at

Morristown National Historical Park. Follow him at https://revolutionarywarmemory.substack.com/.

Tuesday, August 27, 2024

Thomas Jefferson Summarizes his Views

Follow this link to read a post in the Journal of the Americal Revolution about Thomas Jefferson's A Summary View of the Rights of British America.

This post is by Morristown NHP chief of cultural resources Dr. Jude Pfister.

Thomas Jefferson Summarizes his Views - Journal of the American Revolution (allthingsliberty.com)

Image via Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History

Tuesday, May 28, 2024

The Young George Washington and the Skirmish of Jumonville Glen

Earlier

this month we noted Benjamin Franklin’s mention of George Washington in the May

9, 1754 article accompanying Franklin’s famous “Join, or Die” cartoon.

Franklin’s emblem, as such images were called at the time, captured the rising

tensions between British and French colonists who in the 1750s were competing

for land and supremacy in the Ohio River Valley. Franklin was expressing the

need for British colonial unity. Today, in the second installment of our series

on the events of 1754, we highlight the next major episode in the crisis: The Skirmish

of Jumonville Glen. This incident came to be so-called after the wounding and

killing there of Ensign Joseph Coulon de Villiers

sieur de Jumonville.

With the arrival of spring young Washington, now promoted to lieutenant colonel, was again in the field to continue diplomatic and military efforts against the French. With him were not just British colonial troops but men serving under the Native American leader Tanaghrisson, known also as the Half King. Events climaxed on May 28, 1754 when Washington, Tanaghrisson and the men under their command clashed with French forces in rural Pennsylvania. Two hundred and seventy years later the details are still in dispute. Who fired the first shot, and from which side, are just the first issues of contention. Equally unclear are the immediate intentions of the rival parties. Were Jumonville and his men on a peaceful mission on behalf of the French cause, or did they have other, more threatening objectives? Historians still debate these issues over two and a half centuries later. What is clear is that in the fog of battle dozens were killed, wounded, and taken prisoner, especially on the French side. Among the injured was the French commander, Jumonville himself. After the skirmish the Frenchman apparently attempted to speak with Washington and the others through the parties’ translators. Then suddenly, according to some sources, Tanaghrisson killed Jumonville with a tomahawk blow to the head.

The events that took place at what came to be called Jumonville Glen lasted a mere fifteen to twenty minutes. The consequences reverberated across the globe. These were the first shots in what came to be called the French and Indian War in America, and the Seven Years War abroad. British statesman—and historian—Winston Churchill famously called this conflict the first world war, and for good reason. The French, British, and their respective allies fought not just in North America, but on the European and African continents, on the high seas, and in such far-flung places as India before the fighting ended in 1763.

Image / Though this sketch from Alexandre Dumas’s 1855 “La Régence

et Louis Quinze” (volume one) depicts Jumonville being shot by British colonial

forces, most historians believe he was killed by the Native American leader and

warrior Tanaghrisson, known also as Half

King. George Washington’s role, if any, in Jumonville’s killing is unclear and

a matter of debate still today. Credit: Image reworked by Saibo, via Wikimedia

Commons.

Keith J. Muchowski writes occasionally for Morristown National Historical Park.

Friday, May 17, 2024

Featured Object: Thomas Paine’s Hair

Appropriately, in the Morristown National Historical Park’s, Washington Headquarters Museum, Pamphlets of Protest Gallery, resides a new exhibit on the revolutionary rise of the author of one of the most recognized pamphlets of protest in the American Revolution, Thomas Paine. Paine, of course, wrote “Common Sense” among many other recognizable works. “Common Sense” is often credited with helping to raise support for the cause of liberty during the revolutionary period in America.

In conjunction with the release of our blog article on Thomas Paine and his fractured relationship with George Washington we have created a small exhibit that contains, a volume of Paine’s complied writings, as well as a lock of his actual hair, both from the park’s collection.

The hair came to us with solid provenance. In fact, it was attached to a note that explained it all.

It reads:

The

hair was given me by my friend Edward Smith. It is kept in the original paper

in-scribed “Mr. Paine’s Hair” in the handwriting of B. Tilly, Cobbetts agent-

whose handwriting is well known to Edward Smith and myself.”

Moncure

D. Conway

The aforementioned William Cobbett was, according to Joy Masoff, “A harsh biographer of Thomas Paine, Cobbet later recanted and removed Paine’s remains from his New Rochelle gravesite for a grand monument in England that was never built.”[1] Cobbett, the erstwhile critic of Paine’s unfortunately ran out of money and was unable to create the monument he envisioned.

As noted in the letter the hair is affixed to, Cobbett did, in fact, carry “Paine’s body from New Rochelle to England” leading to years of speculation on where in the world various parts of Paine have ended up, including his brain, his bones and even more hair. (Read more on that here from our friends at the Institute for Thomas Paine Studies)

The hair in the Morristown NHP collection seems to have passed through several hands before ending up in New Jersey, as evidenced, once again by all of the names mentioned in the letter. This is what we, in the museum world call provenance, or the history of the ownership of an object.

Essentially the hair passed from William Cobbett to his agent, Benjamin Tilly, to Edward Smith, to Moncure D. Conway to the park, now on display for you to see. Come check it out!Written by:

Holly Marino, Museum Specialist

[1] Masoff, Joy.

2024. “The Curious History of Thomas Paine’s Biographies.” The

Beacon, Vol. 18, No. 3, May, 2024.

Wednesday, May 15, 2024

SOLDIERS STORY: THE SOLDIER BOYS (PART 2)

Officially, a young man during the Revolution could be drafted or volunteer for service at the age of 16, and indeed many young men did so. A few jumped the gun and started their military service at a younger age. We found a few boy soldiers in our Morris County soldiers database, the youngest being only 9 years old when he enlisted in the army. These men (and/or their widows) all applied for and received a pension for their service, which is a significant reason why their stories are preserved. There were surely more young Morris County soldiers whose stories have been lost to time.

After serving in several notable battles including the Canada Expedition, Brandywine, and Monmouth, Jonathan Ford Morris resigned from the army in November 1778, shortly after his father died of a battle wound. He re-enlisted in March 1780 in a new role that was a bit further from the action, serving as a Surgeon’s Mate reporting directly to the Army’s Surgeon General, Dr. William Shippen until June 1782. He and Dr. Shippen remained close friends after the war, and Jonathan Ford Morris followed Shippen’s lead to become a doctor.

Jonathan Ford Morris married Margaret Smith Ewing/Ewen in 1784 and moved to Somerset County, where he set up his medical practice. Jonathan and Margaret raised a large family of nine children. He died in Somerset Co NJ on 13 Apr 1810 and is buried at the Old Presbyterian Graveyard in Bound Brook.

Jonathan Ford Morris’ signature, from his pension

application

Morgan Young Jr. (DAR Ancestor A200275)

Born on 3 Jan 1762 in Mendham NJ, Morgan Young Jr. was about 14 years old when he joined the militia as a Private in 1776. His father also supported the Revolution as a wagoneer.

He served in the Battle of Springfield, an expedition to Staten Island, and battles at Hackensack and Elizabethtown. At Minisink, he guarded the “frontiers against the incursions of the Indians.” He also served as a guard for British prisoners held at Morristown. Historians have reported that he served as a water boy for General Washington, but he did not make any claim of this in his pension record.

He married Jane Losey of Mendham and remained in Mendham for a few years after the war before moving west. He lived for 18 years at Red Stone Fort (currently Brownsville) PA, then moved to Ohio, living in Adams, Huron, and Sandusky Counties before moving further west to Indiana with his son Losey Young.

Morgan Young Jr. died at La Grange IN on 21 Jan 1852. He is buried next to his wife at the United Methodist Church Cemetery in Howe IN. His tombstone reads “Morgan Young Died Jan. 21, 1852 in His 97 Year, A Revolutioner Formerly of New Jersey"

Find-a-Grave Memorial #24741330

Morgan Young’s signature, from his pension

testimony

Moses Johnson

Moses Johnson was born on 17 May 1763 at Hanover Twp NJ. When he was 14 years old, he entered the service as a substitute in June 1777 as a Private in the Morris County militia. He substituted for a number of men, including his uncle Jonas Ward, his father, his neighbor John Tuttle, and David Ogden.

He first served

guard duty in Newark, Acquackanonk, and Morristown at the commissions

storehouse and guarding prisoners at the courthouse. He was also a scout to track Tory

movements. Later in the war, he served

on the Minisink expedition against the Indians, as well as battles at

Springfield, Connecticut Farms, and Elizabethtown.

After the Battle of Connecticut Farms, he testified that his unit was sent to Elizabethtown, where the next day they were ordered to “file off into an open field, where a firing commenced between a scouting party of the militia + British. They were then formed into a line of battle and were ordered to march at quick step toward the woods where the firing commenced. The party then retreated to the enemy fortifications on Elizabethtown point - the part of the militia that had engaged the scouting party of the enemy brought sixteen prisoners to our regiment.”

A few days later at the Battle of Springfield, he reported that “he was on a road north of the village about half a mile when the battle began. After the village was set on fire the British retreated to Elizabethtown point and crossed over to Staten Island. His Regiment with the militia + Regulars went down the same night and destroyed the fortifications a few days after the British retreated.”

Serving more guard duty in Morristown in August 1780, he reported that “there were about 52 Tories brought to Morristown and confined in the jail there. They were tried in the Presbyterian Meeting House in that place…there were thirty five of them sentenced to die hanged – only two were hanged…”

He moved to Tioga, Onandaga, and Ontario counties in New York. He was last known living in Angelica, Allegany County NY in 1832, where he applied for a pension. His death and burial are unknown.

Moses Johnson’s signature, from his pension

testimony

Thomas Layton was born in Morristown NJ on 11 May 1765. When he was young his family moved to Northumberland County PA, where he enlisted in the militia in 1777 at the tender age of only 12 or 13.

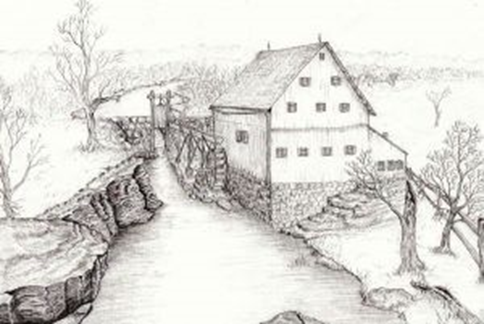

He was stationed at a settlers’ fort known as Boone’s Fort near Milton PA, serving under Captain Hawkins Boone who is said to be a cousin of Daniel Boone. The fort was the site of a grist mill which had been fortified during the Revolution. Being at the edge of the frontier, the area was subject to frequent attacks by the British Army, loyalists, and Native Americans aligned with the British. Beyond this point there was no colonial government and no protection except for privately owned settlers’ forts.

The grist mill at Boone’s Fort, from

https://www.legendsofamerica.com/boones-fort-pennsylvania/

The most notable

fort in the area was Fort Freeland, the site of a bloody and pivotal incident

which young Thomas Layton witnessed first-hand.

In June 1779 several families fled to Fort Freeland for protection against

the frequent attacks. Though there had

been rumblings of another pending attack, 21 boys and old men defending the

fort were caught by surprise when 300 British soldiers and supporters stormed

Fort Freeland on 28 Jul 1779. When

Captain Boone heard of the attack, he rushed his company to defend Fort

Freeland, including Thomas Layton.

Captain Boone and other officers were killed in the ensuing battle,

along with about half the men. About

20-25 men were taken to Canada as prisoners.

A few men managed to escape, but 13 of their scalps were brought back in

a handkerchief. The fort was burned,

leaving the frontier largely defenseless, and most of the remaining settlers

left the area until after the war.

Fort Freeland, from https://www.legendsofamerica.com/boones-fort-pennsylvania/

Thomas Layton

continued his service even after the harrowing experience at Fort Freeland. He joined the Pennsylvania state troops when

he came of age, and remained in service until he was discharged in December

1783. His service consisted primarily of

guarding the inhabitants against the Native Americans, or tracking the Native

Americans as an “Indian Spy.”

In his pension testimony, he described being provisioned clothing from the state of Pennsylvania when he was part of the state troops. As a rifleman, he was provisioned a short blue coat with white trim. Their officers wore blue coats with red facing and trim. He also described being provisioned powder and lead, but they had to remake all of the lead balls to fit their rifles.

At one point his unit went on an expedition to “Ealtown” with 350 men. But he reported that “the Indians had heard of our coming + had left their town. We burnt the town + then came home…”

Thomas Layton moved to New York in 1791, then moved to Clark County IL around 1804. He applied for and received a pension in 1833. His final pension payment was dated 3 Sep 1841 and died some time after that, though no further details of his death or burial are known.

Thomas Layton’s signature, from his pension

testimony

Sources

Find-a-Grave Memorial #244502757, Moses Johnson

Find-a-Grave Memorial #147925086, Thomas Layton

Find-a-Grave Memorial #52993873, Dr. Jonathan Ford Morris

Find-a-Grave Memorial #24741330, Morgan Young, Jr.

Buckalew, John M., The Frontier Forts Within the North and West Branches of the Susquehanna River, Vol. 1 of the Report of the Commission to Locate the Site of the Frontier Forts of Pennsylvania by Clarence M. Busch, 1896, online at http://www.usgwarchives.net/pa/1pa/1picts/frontierforts/ff15.html

https://www.legendsofamerica.com/boones-fort-pennsylvania/

U.S. Revolutionary War Pension W787, Abraham Fairchild, National Archives and Records Administration, M804, Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, RG15

U.S. Revolutionary War Pension S13551, Moses Johnson, National Archives and Records Administration, M804, Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, RG15

U.S. Revolutionary War Pension S32371, Thomas Layton, National Archives and Records Administration, M804, Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, RG15

U.S. Revolutionary War Pension W135, Jonathan Ford Morris, National Archives and Records Administration, M804, Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, RG15

U.S. Revolutionary War Pension S4741, Morgan Young, National Archives and Records Administration, M804, Records of the Department of Veterans Affairs, RG15

Monday, May 6, 2024

Join or Die

"Friday last an Express arrived here

from Major Washington, with Advice, that Mr. Ward, Ensign of Capt. Trent's

Company, was compelled to surrender his small Fort in the Forks of Monongahela

to the French, on the 17th past;”

So began an article in the May 9, 1754 edition of Benjamin Franklin’s “Pennsylvania Gazette” announcing that Ensign Edward Ward of Captain William Trent’s company had surrendered his small, hastily constructed fortification in what is today Pittsburgh to a larger French force on April 17th. The major mentioned is George Washington, a young colonial officer increasingly embroiled in the British struggle with the French for control of North America. The latest struggle had been escalating for six months, when in October 1753 Virginia Lieutenant-Governor Robert Dinwiddie sent Washington to Pennsylvania to negotiate with the encroaching French. Washington returned in January empty handed. In February, to underscore the seriousness of the escalating crisis, Dinwiddie published the notes of Major Washington’s nearly 1000-mile expedition and printed them in pamphlet-form as “The Journal of Major George Washington, Sent by the Hon. Robert Dinwiddie, Esq; His Majesty's Lieutenant-Governor, and Commander in Chief of Virginia, to the Commandant of the French Forces on Ohio.” Washington’s “Journal” was subsequently published in newspapers throughout the colonies and reprinted in London several months later, where it was read with great interest by many leading figures of the British empire.

George Washington, still just in his early twenties, was making a name for himself on both sides of the Atlantic. Now that spring was again here, Dinwiddie promoted Washington to lieutenant colonel and sent him back to Pennsylvania to deal again with the French. That is how Washington’s message describing Ensign Ward’s surrender at the Monongahela was published in the “Pennsylvania Gazette.”These were all crucial events in Colonial American history, but what makes the article in the May 9, 1754 edition of Franklin’s newspaper even more important to us today was the inclusion of the accompanying “Join, or Die” political cartoon we see here.

It was one of the very earliest political cartoons published in American history. We say “one of the earliest” because there is a misconception in some circles that the “Join, or Die” cartoon is the very first. This is untrue. In November 1747 Benjamin Franklin himself had published a cartoon within a political pamphlet entitled “Plain Truth” that he had written and published anonymously as “a Tradesmen of Philadelphia” describing the state of affairs as he saw them in his city and colony.

Franklin in “Join, or Die” was calling for unity amongst British colonial subjects in the struggle against the French and their Native American allies. The cartoon was reprinted in several colonial newspapers within weeks after its initial publication. The serpent itself is a compelling choice. For one thing, the snake roughly delineates the cartography of the British colonies along the Eastern Seaboard, with New England at the head and South Carolina at the tail (Georgia being excluded). That it is a dismembered snake is also of note. British subjects in North America had always been split, with most inhabitants of the different colonies believing they shared more in common with the mother country across the Atlantic than with the residents of their neighboring provinces. Many in Franklin’s time believed that a serpent cut into pieces could rejoin its parts into a cohesive whole. Franklin’s inspiration for the dismembered snake was likely an “emblem” engraved by the French graphic designer Nicolas Verien in his 1685 book “Livre Curieux et Utile Pour Les Sçavans et Artistes.” Verien’s engraving depicts a dissected snake with the accompanying text reading “Un serpent coupé en deux. Se rejoindre ou mourir.”

British colonists in North America joining together in unity was long a goal of Benjamin Franklin. That very spring he was helping to organize what became the Albany Congress, a convention of officials from seven colonies who from June 19—July 11, 1754 met in Albany, New York to discuss a potential plan of union. In attendance too were representatives from the Six Nations of the Iroquois Confederacy, with whom Franklin and the others were hoping to improve relations. Little came from the Albany gathering. Indeed, by the summer of 1754 even as they were meeting further military engagements between the British and French were already underway. The French and Indian War would last until 1763 with the British ultimately victorious. Benjamin Franklin’s “Join, or Die” cartoon has been repurposed continually in the nearly three centuries since its publication two hundred and seventy (270) years ago this month. Colonists used it in protest against British taxation during the 1765-66 Stamp Act crisis. Patriots throughout the American Revolutionary War created numerous variations upon Franklin’s image and accompanying text. The yellow Gadsden Flag with its coiled snake and “Don’t Tread on Me” warning is but one example.

More broadly, political cartoons became part of the American vernacular. For instance in the early 1870s William Magear Tweed, the political boss who controlled New York City’s Tammany Hall, pleaded for someone—anyone—to “Stop them damn pictures.” The “pictures” that so enraged Boss Tweed were the political cartoons created by Thomas Nast and published in “Harper’s Weekly” exposing the corruption of Tweed and his henchmen. Tweed noted that many of his constituents were themselves illiterate and thus could not read political exposés, but that there was simply no competing with the visual imagery of the cartoons that lampooned him so pithily. Benjamin Franklin had been gone for more than eighty years by this time, but he would have understood Tweed’s sentiments. As a publisher Franklin grasped the power not just of the written word, but of visual imagery itself. That is why he published “Join, or Die” in his “Pennsylvania Gazette” on May 9, 1754 to begin with. In doing so, he laid the foundation of yet another aspect of American culture and iconography.

Images:

Published in Williamsburg, Virginia in

February 1754 the month that George Washington turned twenty-two and reprinted

in London later that year, the “Journal” brought Washington to national and

international prominence in the early months of the French and Indian War.

William Hunter was Virginia’s official printer, publisher of the “Virginia

Gazette,” and since 1753 deputy postmaster general for the British North

American colonies along with Benjamin Franklin.

The “Join, or Die” cartoon, or “emblem”

as such images were called at the time, as it appeared in Franklin’s “Pennsylvania

Gazette” on May 9, 1754.

Nicolas Verien’s “Un serpent coupé en deux. Se rejoindre ou mourir.” appeared in the engraver’s 1685 emblem book “Livre Curieux et

Utile Pour Les Sçavans et Artistes.”

Keith J. Muchowski is a volunteer with

Morristown National Historical Park. This is the first in what will be an

occasional series marking events that occurred in 1754 at the outbreak of the

French and Indian War.

.jpg)

.jpeg)