Before my time at Morristown National Historical Park, I was one of the many people who had been enamored with the musical Hamilton. As a history and political science student with an interest in theatre, the story of Alexander Hamilton in musical form seemed to be everything I could have ever hoped for. So, when the question of what my summer internship project would be was raised, the answer seemed clear: create an exhibit featuring the manuscripts of Alexander Hamilton in the museum’s collection.

Before my time at Morristown National Historical Park, I was one of the many people who had been enamored with the musical Hamilton. As a history and political science student with an interest in theatre, the story of Alexander Hamilton in musical form seemed to be everything I could have ever hoped for. So, when the question of what my summer internship project would be was raised, the answer seemed clear: create an exhibit featuring the manuscripts of Alexander Hamilton in the museum’s collection.

While the end goal seems clear, the process of constructing and researching an exhibit has many different components and goes through different phases. Luckily, Alexander Hamilton has always been a well-known figure to historians, even though the public just took interest in him recently. So, there was a solid foundation of information to start. The first step was determining which manuscripts would be featured in the exhibit. Morristown’s collection currently contains eighty-two documents authored by Hamilton. Luckily, the manuscripts are cataloged in a digest containing their basic information and brief summary of their contents. This made my search easier because I didn't have to track down eighty-two individual documents in order to begin.

With the help of three different color highlighters, I was able to decide which documents the most were interesting or came from defining parts of Hamilton’s life.

From the summaries in the

digest, my next step was to look as the letters on the museum’s microfilm to

examine the entire letter. My first round of searching discovered that our

manuscripts are truly representative of Hamilton’s entire life, from the Revolutionary

War, his private law practice, his time as Secretary of the Treasury, his

service as Inspector General of the United States Army, and even his own

property. I decided on six letters to focus on. My choices were a letter to

Colonel Pickering from 1780, a letter to Philip Schuyler from 1781, a report to

George Washington from 1794, two letters to James Monroe from 1797, and a

letter to Elizabeth Hamilton from 1798.

While

having these documents is the best way to look into Hamilton’s life, I knew I needed

to find more information in order to create a full picture of Alexander

Hamilton, not only for anyone looking at my display, but for myself as well.

Now, I thought I had a pretty solid understanding of Hamilton through my

admiration of the musical and my previous knowledge. However, off I went into

the realms of the internet to see how well I really knew Alexander Hamilton and

I discovered that there was more to this founding father than any one musical

could ever cover. I spent multiple days simply combing through article after

article in order to put together a detailed, cohesive timeline of Hamilton’s

life. I even color coded the timeline I made, giving different events in his

life different colors, from Revolutionary War achievements to his personal

life, in order to see how many different facets Hamilton’s life was carved into

at any given time.

While

having these documents is the best way to look into Hamilton’s life, I knew I needed

to find more information in order to create a full picture of Alexander

Hamilton, not only for anyone looking at my display, but for myself as well.

Now, I thought I had a pretty solid understanding of Hamilton through my

admiration of the musical and my previous knowledge. However, off I went into

the realms of the internet to see how well I really knew Alexander Hamilton and

I discovered that there was more to this founding father than any one musical

could ever cover. I spent multiple days simply combing through article after

article in order to put together a detailed, cohesive timeline of Hamilton’s

life. I even color coded the timeline I made, giving different events in his

life different colors, from Revolutionary War achievements to his personal

life, in order to see how many different facets Hamilton’s life was carved into

at any given time.

While so many people know

about his larger achievements, such as serving at the Constitutional

Convention, what fascinated me the most is that there was always something

going on in his life, whether public or private, large or small.

Now fully equipped with

knowledge, it was time to decide how I could organize the letters and what kind

of story I wanted to tell. As my letters span multiple years and topics, it

would be hard to try and tell Hamilton’s entire life story without straying

from the amazing original material we have in the collection. So, I decided to

frame this exhibit as snapshots of Hamilton’s life, giving it a temporary name

of “Hamilton’s Most Memorable Years”. My next step was to take each letter and

dissect it for interesting quotes and references, as well as placing it in

Hamilton’s life (basically how or why this letter exists). As I started this

phase, I decided that Hamilton’s report to Washington would not become part of

my exhibit. As interesting as it is, the report is not about an event that

Hamilton or Washington are directly involved in and would take away from

sharing Hamilton’s life and times. Also, the report is fourteen pages long….so

out it went.

Five single spaced pages

later, I had laid out the five letters and their importance to Hamilton. I was

ready to start shaping my exhibit and brochure. However, before I could do

anything, I knew I needed a new title, since “Hamilton’s Most Memorable Years”

sounded more like cheesy sitcom or TV movie than an exhibit. As I looked at the

letters, one quote stood out. In the 1781 letter to Philip Schuyler, Hamilton

refers to “some plausible pretext” as a way that some individuals will tell a

story. While building this exhibit, I am essentially using my own “pretext” to

tell Hamilton’s story, but that “pretext” is Hamilton’s own words and thoughts

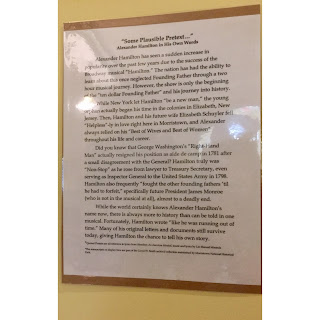

expressed in these letters. My exhibit took the name:

As my brochure started to take shape, I noticed

that I was still missing an overview element to Hamilton. While the letters and

their secondary information were insightful, I still wanted anyone who saw the

exhibit to be able to know how this letter fit into Hamilton’s story (to know

what came before and after). In one of my check-in meetings with Dr. Jude

Pfister, he suggested a timeline to serve as an introduction before the real

“meat” of my exhibit. Since I already had my extensive, color-coded timeline,

it was easy to condense and create another one to fit in the brochure, this one

highlighting the years of the letters that would be on display; 1780,1781,1797,1798.

Another important part of creating an exhibit is

creating an introductory text panel to catch the attention of visitors and

describe what they would be looking at. Given Hamilton’s current popularity,

there is already certain level of attention given when he is mentioned.

However, my concern was that, what if people had the same mindset I did when I

first started my research? That the musical Hamilton already educated a person

enough and that this would be restating some of those points? So, I decided to put my knowledge of the

musical to good use and play on the song titles and lyrics, mixing what the

musical explains and what the audience does not get through the music.

Another important part of creating an exhibit is

creating an introductory text panel to catch the attention of visitors and

describe what they would be looking at. Given Hamilton’s current popularity,

there is already certain level of attention given when he is mentioned.

However, my concern was that, what if people had the same mindset I did when I

first started my research? That the musical Hamilton already educated a person

enough and that this would be restating some of those points? So, I decided to put my knowledge of the

musical to good use and play on the song titles and lyrics, mixing what the

musical explains and what the audience does not get through the music.

After the text was finished,

I finally emerged from behind my computer and began the assembly phase, a much

more physical part of the exhibit building process. This phase included Dr.

Sarah Minegar and I pulling my selected manuscripts, which meant spending one,

almost two days going through boxes in the archives (and finding a lot of cool

stuff along the way).

Once the manuscripts were ready to display, my fellow intern Claire (who was working on a World War I exhibit during this time) and I transferred our empty display cases up to the main floor of the museum (they do not fit in the elevator…trust me…we tried). Then, it was time to find the perfect way to display all of the manuscripts, which contained a lot of trial and error placement until I was satisfied.

This part of the process sounded easy at first,

but proved to have its own challenge; the curious eyes of visitors constantly

watching to see what this new addition is in the front of the museum. Once the

exhibit was finished, that curiosity turned to excitement at the opportunity to

learn about something new opened in front of them.

The visitors were not the

only ones experiencing something new, as a first time exhibit designer, this

project allowed me to take someone, like Alexander Hamilton and not only expand

my knowledge, but share it with others as well. While it was not always easy,

for instance, coming across missing manuscripts and mismarked documents (those

stories are for anther blog post). Overall, I was able to learn something along

the way, which is the point of coming to a museum in the first place.

This blog post by Meghan Kolbusch, Centenary University.

No comments:

Post a Comment